TRAFIC

TRAFIC es un modelo de furgoneta.

TRAFIC es una serie de exposiciones que tienen lugar en una furgoneta.

TRAFIC sigue siempre el mismo patrón: Duración de apenas unas pocas horas, según unas fechas decididas de forma aleatoria y allí donde se haya encontrado plaza de aparcamiento en la montaña de Montjuic de Barcelona.

Eloi Rodríguez Romeu es un recién graduado en Artes y Diseño que trabaja en una empresa de Smart Delivery subcontratada por Amazon en la que ejerce como repartidor en furgoneta.

--------------------

El proyecto Trafic se inserta en las dinámicas de trabajo y producción del Grup d’Estudi, un grupo que se ocupa del trabajo de catalogación y de proposición de nuevas formas de presentación pública de las producciones artísticas, y que defiende la radical movilidad, respecto de la adscripción al grupo, de sus integrantes.

The New York Times

Are You an Anti-Influencer?

Some people have a knack for buying products that flop, supporting political candidates who lose and moving to neighborhoods that fail to thrive.

What do Crystal Pepsi, Watermelon Oreos, Frito-Lay Lemonade, Coors Rocky Mountain Sparkling Water, Colgate Kitchen Entrees and Cheetos Lip Balm all have in common?

The obvious answer is they are all failed products. What is less obvious is that they may also share a fan base — a quirky subgroup of consumers who are systemically drawn to flops and whose reliably contrarian tastes can be used to forecast bad bets in retail sales, real estate and even politics. These people are known as “harbingers of failure.”

The study of harbingers emerged from a 2015 analysis of purchasing patterns at a national convenience store chain. (In exchange for the data, the researchers agreed not to reveal the identity of the chain.) Drawing on six years’ worth of data from the chain’s loyalty card program, a team of marketing professors led by Eric Anderson of Northwestern University classified customers according to their affinity for buying new products that were later pulled from the shelves because of weak demand. Of the roughly 130,000 customers whose purchases were logged, a sizable fraction (about 25 percent) consistently took home products that bombed.

“It was really an accident,” says the economist Catherine Tucker of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, one of the study’s authors. “We looked in the data and saw there were some customers who were really good at picking out failures” — so good, in fact, that a newly introduced product was less likely to survive if it attracted these buyers. (And if they bought it repeatedly, its chances of survival were even worse.) Professor Tucker called these people harbingers of failure because, statistically speaking, their fondness for a product heralded its demise.

The harbinger effect has since been shown to apply not just to individuals but also to geographic locales. In a paper published last year, the M.I.T. marketing professor Duncan Simester documented the existence of harbinger ZIP codes — areas of the country that consistently go for unsuccessful new products. Like individual harbingers, these ZIP codes are canaries in the coal mine for ill-fated offerings. Be it a newfangled flavor of soft drink or a recently released line of jeans, early adoption of a product by households in these ZIP codes augurs grimly for its future.

And the phenomenon goes beyond retail sales. Working with the political economist Clair Yang of the University of Washington, Professors Tucker and Simester compared the contributions to congressional campaigns made by harbinger ZIP codes — identified, again, through their purchasing decisions — with those made by neighboring ZIP codes over the course of five federal election cycles. They found that harbinger ZIP codes prefer to donate, in both absolute dollars and total number of donations, to candidates who end up losing their races.

“This was very surprising to us,” Professor Yang says. “Politics is as far away from consumer products as possible. If someone likes Coke instead of Pepsi, that shouldn’t affect whether they’re a Republican or a Democrat.”

The existence of harbinger ZIP codes was a surprise, admits Professor Simester, who initially assumed that the phenomenon was a byproduct of households’ absorbing the preferences and habits of their neighbors — a phenomenon that has been demonstrated in numerous other contexts. “My expectation was that these people are learning from each other,” he says.

To test this assumption, Professors Simester, Tucker and Yang evaluated data on 30,000 households that changed ZIP codes within a four-year period. Their analysis showed that when households in harbinger ZIP codes moved, they tended to move to other harbinger ZIP codes, while households in nonharbinger ZIP codes did the opposite.

Professor Simester and his colleagues then compared the buying habits of households before and after they moved, to see if transitioning to a new area affected them. It didn’t. Even when harbingers moved to a neighborhood of nonharbingers, their disaster-prone tendencies persisted. They didn’t rub off on their neighbors, either. “If you’re not a harbinger and you accidentally move into a harbinger ZIP code, you don’t start buying strange products,” Professor Tucker explains.

This remarkable finding suggests that the clustering of harbingers at the ZIP code level is a result not of social learning but of water seeking its own level. Evidently, the same irregular drumbeat that harbingers march to while browsing the aisles of supermarkets and private label clothing stores also guides their decisions about where to live, leading them to the same neighborhoods.

And as with their tastes in soda and jeans, these decisions have a predictably gloomy result: Property values in harbinger ZIP codes consistently underperform the broader market, according to an analysis of changes in housing prices across more than 4,000 ZIP codes over 12 years.

Being a dowsing rod for disappointments, moreover, appears to be a curiously stable attribute, a “sticky” trait that is transported but not transmitted and doesn’t bow to shifting social norms. “It’s not a contagious thing,” Professor Tucker says. “It’s an inherent characteristic.”

But what exactly is that characteristic? Who are the harbingers?

Attempts to characterize these people have borne little fruit. The harbingers are slightly more concentrated on the West Coast and in nonurban areas, demographic data has shown, but other than that they exhibit no clear geographical pattern. They may be a little wealthier than average and have bigger families, although the evidence for that is open to doubt. They shop at warehouse clubs like BJ’s and Costco — but then, who doesn’t? And they’re big on variety: Harbingers buy a wide assortment of brands but make fewer repeat purchases than the average consumer, which may explain why demand from harbingers alone isn’t enough to sustain the products they acquire.

That’s the closest thing to a composite sketch researchers have been able to draw, and admittedly it leaves many questions unanswered. Perhaps, Professor Tucker suggests, harbingers are simply on a different wavelength from the rest of us. “I think what we’re picking up on is that there are just some people who, for whatever reason, have consistently nonmajority tastes,” she says, noting that in addition to buying short-lived products, harbingers buy a lot of niche items. “They like that odd house. That political candidate everyone else finds off-putting. They like Watermelon Oreos.”

Even if we aren’t sure what makes harbingers tick, we can still learn from them. For one thing, they may help us understand why many products that debut to strong sales and positive customer feedback wind up tanking, a problem that has long confounded marketers. “If you want to predict which products are going to be successful, you don’t just want to look at total sales,” Professor Simester says. “Look at who’s buying.”

Analyzing data from harbingers could also help generate more accurate political forecasts and sounder real estate investments. Currently, Professor Tucker is exploring the possibility of applying harbinger metrics to finance.

But it’s the human angle of the harbinger research that most intrigues her. “It resonates with so many people,” Professor Tucker says. “Everyone knows that one person. Or they are that person. And for them I’ve suddenly explained their life.”

Alex Stone is the author of “Fooling Houdini: Magicians, Mentalists, Math Geeks and the Hidden Powers of the Mind.”

Idees conceptuals pel projecte a la galeria Aurora:

- Loosers i winners de l’art. Èxit professional o dedicar-se a l’educació. (èpica)

- Rendibilitzar un projecte del qual no s’ha cobrat però si que ha produït en el marc d’una beca (professionalització).

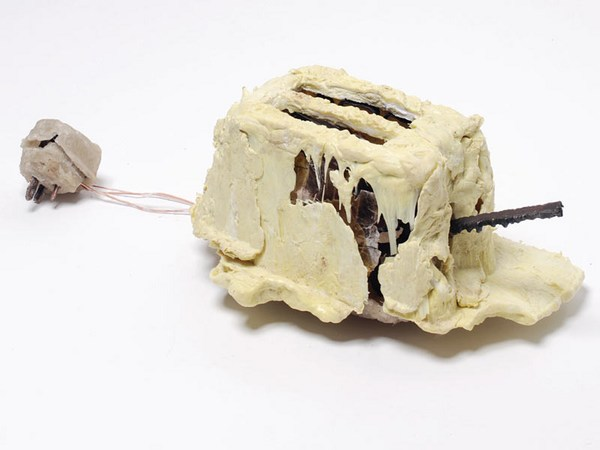

- Versemblança de certes formalitzacions artístiques que intenten semblar una cosa a través d’una altra cosa, com un resultat que sembla d’un material pesat però que està fet d’un material lleuger. El mèrit a través de la ficció. Com les plaques de pòrex de l’Eulàlia, que semblen pladur.

- Imitació (o no) del llenguatge de l’Educació Visual i Plàstica de l’escola i els tallers d’art. Amateurisme de la professionalització artística o reproducció d’una estètica amateur. Tothom és artista (?).

- Reproduir certs objectes que han format part de la quotidianitat en la que ens hem conegut.

- Hi ha dos tipus de formalitzacions amateurs a)Les que són possibles perquè requereixen de pocs mitjans; b)Les que són una alternativa a un procés que requereix molts mitjans i per tant no és accessible (objectiu versemblança).

- Realitzar un procés molt tècnic (que requereix molts mitjans) per elaborar una formalització molt amateur (que no requereix molts mitjans).

- Entre diferents membres del Grup d’Estudi, ens uneixen aspectes que responen a la reproducció tant de la vida quotidiana com la professionalització de l’art. Com un entrevista per compartir pis, muntar i desmuntar l’exposició individual d’un altre membre del grup, compartir cotxe per anar a un esdeveniment d’art fora de Barcelona, traspassar el lloguer d’una habitació, estudiar un màster per ser professor d’art, participar en una proposta comissarial d’un membre del grup rebutjada en una convocatòria, entre d’altres. Relacions que són com un gag d’una sitcom de l’art.

- Sitcom: La caixa de la tele coincideix amb la caixa del plató. El públic in situ veu teatre, qui ho veu per la tele veu una realitat. Existeixen un conjunt de mecanismes que contribueixen a construir aquesta versemblança i ajuden a suggestionar els efectes del producte: riures, plors i altres efectes sonors enllaunats, actuacions prèvies que posen el públic a to (com els Fluffer de les pelis porno que mantenen l’erecció dels actors entre toma i toma).

- L’espai de l’exposició és un túnel que porta a una altra exposició solo show de l’artista que proposa la galeria per Art Nou (una artista més winner).

- L’exposició potser no podrà rebre gent o haurà de entrar-hi sota uns protocols concrets de seguretat sanitària. L’expo pot ser com un Peep show o una sitcom, o pot ser virtual, o pot menester d’un EPIS concret.